What Children Know That AI Doesn't: Learning Through Experience, Not Text

A toddler drops a toy. It falls. They drop it again. By the third time, they predict the fall before releasing. Drop a helium balloon, and watch their delighted confusion—it floats upward instead. This simple interaction contains a profound lesson: the child is building a causal model of gravity through direct experience, learning from genuine surprise when reality violates predictions.

Now consider GPT-4. It has “read” millions of descriptions of falling objects and can generate fluent text: “when you drop something, it falls due to gravity.” But it has never experienced releasing an object, never felt acceleration, never been surprised by a balloon floating. It predicts what would be said about dropping objects, not what would actually happen.

This distinction—between linguistic pattern matching and genuine causal understanding grounded in experience—reveals why current AI, despite impressive capabilities, lacks true intelligence.

Piaget’s Core Insight: Knowledge is Constructed Through Experience

Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development offers a framework for understanding what’s missing. He made a revolutionary claim: children don’t passively absorb knowledge. They actively construct understanding through interaction with the world.1 Knowledge isn’t transmitted—it’s built by the learner through experience, experimentation, and adaptation.

This has immediate implications for AI. Current machine learning follows a transmission model: massive datasets encode patterns, models absorb them through optimization. But a child doesn’t need millions of examples to understand gravity—they construct the concept through dozens of hands-on experiments, generalizing from minimal data by building causal models, not memorizing correlations.

Schemas: Testable Mental Models

Piaget introduced schemas—organized patterns representing our understanding of the world.2 A schema isn’t stored knowledge; it’s an active framework for interpreting experiences, making predictions, and recognizing when reality violates expectations.

A child’s schema for “dog” includes: four legs, fur, barks. When they encounter a cat, their dog schema fails to predict its behavior (meows, acts aloof), triggering learning. The schema is testable against reality.

Modern AI has representations—word embeddings, neural activations—but these lack causal structure, predictive power, and testability. They capture statistical patterns, not causal understanding.

Two Modes of Learning: Assimilation and Accommodation

Assimilation: Fitting new experiences into existing schemas. Seeing a new dog breed: “that’s also a dog.”

Accommodation: Restructuring schemas when experiences don’t fit. Meeting a cat: the child must split their schema—dogs AND cats, both with four legs but different behaviors.3

Most neural networks only assimilate—fitting new data within existing capacity. When truly novel information arrives, they fail catastrophically, overfit, or suffer catastrophic forgetting. Few AI systems have mechanisms for graceful accommodation—recognizing when their world model is fundamentally wrong and restructuring it while preserving valuable knowledge.

The Four Stages: From Action to Abstraction

Piaget proposed that cognitive development progresses through four distinct, universal stages, each characterized by fundamentally different ways of thinking and interacting with the world.4

Stage 1: Sensorimotor (0-2 years)

Children learn through direct sensory experience and motor action.5 Key achievement: object permanence—things exist even when unseen. This requires repeated experimentation, sensorimotor feedback, and surprise learning. Infants master causality and object permanence by manipulating their surroundings and learning from the consequences.6

For AI: This is the embodiment problem. Systems trained on text or static images lack sensorimotor grounding, action-consequence loops, and physical intuition. They reason about physics they’ve never experienced.

Stage 2: Preoperational (2-7 years)

Symbolic thinking emerges—using words to represent objects not present.7 But limitations remain: difficulty reversing operations mentally, focusing on one aspect while ignoring others (centration), inability to take others’ perspectives (egocentrism).

For AI: This is where LLMs operate. They manipulate symbols fluently but show systematic limitations—sensitivity to surface features, difficulty with logical reversibility, brittle performance when prompts change slightly.

Stage 3: Concrete Operational (7-11 years)

Logical reasoning develops—but only with concrete, tangible examples.8 Children can classify hierarchically, understand conservation (quantity remains constant despite changes in appearance), reverse operations mentally. But they struggle with abstract concepts and hypothetical reasoning.

For AI: Current systems rarely reach this stage. LLMs sometimes simulate logical inference through pattern matching but lack stable, consistent logical frameworks.

Stage 4: Formal Operational (12+ years)

Abstract reasoning, hypothesis testing, scientific thinking.9 Understanding abstract concepts, reasoning about hypotheticals, thinking about thinking (metacognition).

For AI: The unreached goal. Even frontier systems show brittle, domain-specific reasoning that doesn’t transfer robustly.

Three Critical Gaps

Gap 1: Experience vs. Description

Piaget: Knowledge comes from acting on the world and observing consequences. A child learns “hot” by experiencing heat, connecting sensation to cause. Cognitive development emerges from the interaction between the child’s actions and the environment’s responses.10

Current AI: Learns from descriptions of others’ experiences. An LLM has read “fire is hot” millions of times but never experienced heat. It predicts what people say about heat, not what heat actually feels like or causes.

As Alan Turing observed, true machine intelligence requires “machines that can learn from experience, where experience means things that actually happened.”11 Current LLMs lack this experiential grounding—they absorb descriptions, not reality.

Gap 2: Predicting Reality vs. Predicting Words

World Models predict what will happen in reality. A child’s world model: “If I release this, it will fall.” This prediction is tested against reality. When surprised (balloon floats), the model updates.

| LLMs predict what would be said about reality. They model P(next words | previous words), not P(outcomes | actions). When their linguistic prediction is wrong, they receive no feedback from reality—only more text descriptions, which themselves might be incorrect. |

Consider:

Child: "If I let go, this will fall"

→ Action: Releases object

→ Reality: Object falls

→ Update: Prediction confirmed

LLM: "Objects fall when dropped"

→ Action: None

→ Reality: No interaction

→ Update: Only from more text

The LLM’s knowledge is untested and untestable against physical reality.

Gap 3: Learning from Surprise

Piaget’s deepest insight: Children learn most when reality violates predictions. The balloon floats (violating gravity schema), ice melts (violating object permanence), the friendly dog bites (violating behavioral schema). Surprise triggers accommodation—the unexpected outcome signals “my model is wrong.”12

Current AI cannot be genuinely surprised by reality. LLMs never interact with the physical world. When deployed, if predictions are wrong, they receive no reality-based feedback—only human corrections encoded as more text. When an LLM confidently predicts something physically impossible, reality never corrects it.

This is perhaps the most critical limitation: without the ability to be surprised by reality, AI cannot truly learn from experience.

What This Means for Building Better AI

Piaget’s framework suggests several principles:

Start with embodiment: Intelligence should be grounded in sensorimotor experience before abstract reasoning. Train agents in physical environments with action-consequence feedback.

Enable genuine surprise: Systems need to form explicit predictions about reality, test them through action, recognize failures, and use surprise as a learning signal.

Support accommodation: Systems need structured representations that can be updated incrementally or restructured fundamentally, avoiding catastrophic forgetting.

Progress through stages: Follow Piaget’s progression—sensorimotor grounding, then symbolic representation, concrete logic, and finally abstract reasoning. Skipping stages creates surface-level capabilities with fundamental limitations.

The Coming Paradigm Shift: From Human Data to Experience

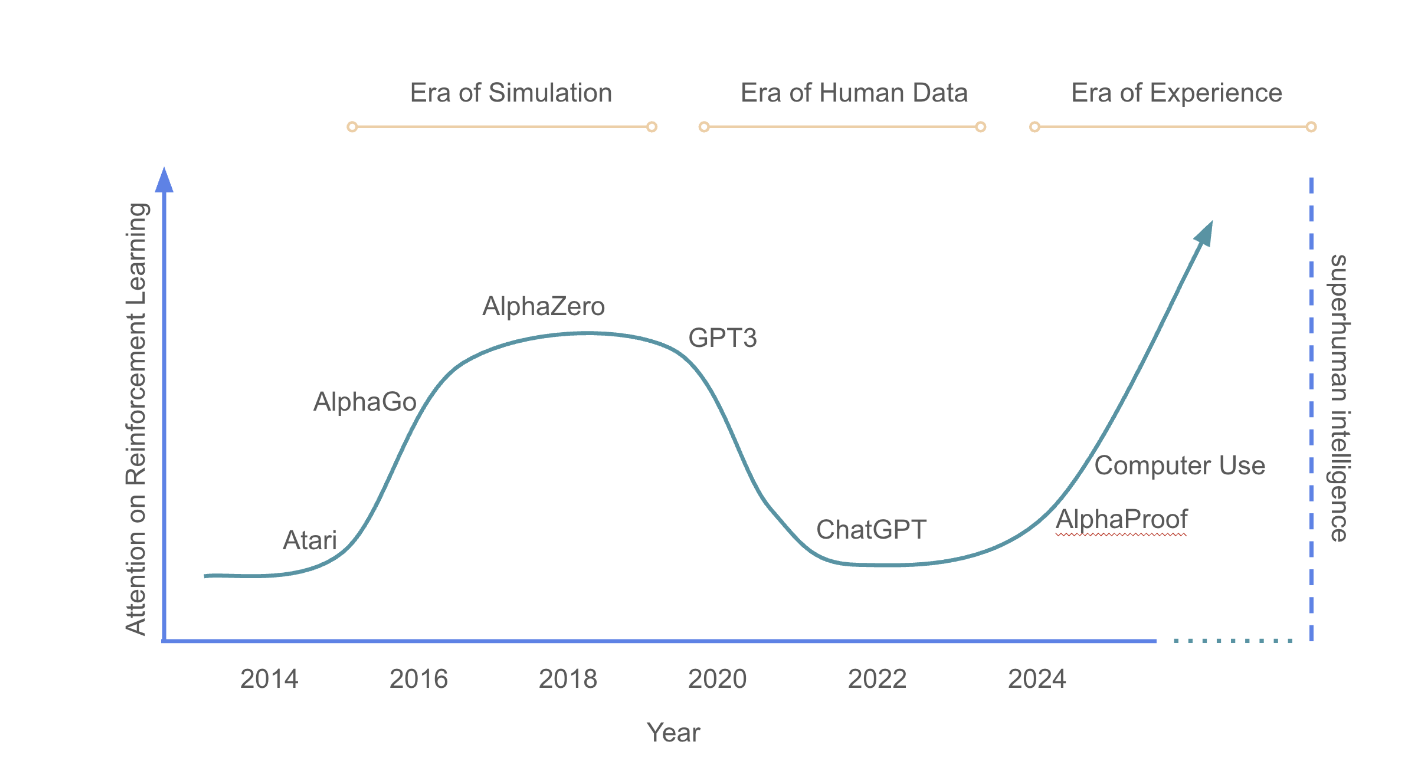

The history of AI reveals a striking pattern. As Silver and Sutton document, we’ve moved through distinct eras: early symbolic AI, the “Era of Simulation” (where reinforcement learning agents mastered games like chess, Go, and StarCraft through self-play), and most recently, the “Era of Human Data” (where large language models trained on massive text corpora achieved unprecedented breadth of capabilities).13

Figure: A chronology of dominant AI paradigms showing the transition from the Era of Simulation (narrow domains, clear rewards) through the Era of Human Data (broad capabilities from text) to the emerging Era of Experience (experiential learning at scale). Adapted from Silver & Sutton (2025).13

Each transition brought gains and losses. The Era of Simulation produced agents like AlphaZero that discovered fundamentally new strategies—knowledge that went beyond human understanding. But these systems were confined to narrow domains with clear reward signals. The Era of Human Data achieved remarkable generality but lost the ability to self-discover knowledge. As Silver and Sutton observe: “something was lost in this transition: an agent’s ability to self-discover its own knowledge.”13

Current AI faces a fundamental ceiling: you cannot learn what humans don’t know by reading what humans have written. In domains like mathematics, coding, and science, we’re rapidly exhausting high-quality human data. More critically, breakthrough insights—new theorems, technologies, scientific discoveries—lie beyond current human understanding and cannot be captured in existing training data.13

The solution? A return to experiential learning, but now applied to open-ended, real-world problems rather than isolated games.

The Four Pillars of Experiential AI

Silver and Sutton identify four critical dimensions that distinguish experiential learning from the current human-data paradigm:13

1. Streams of Experience: Rather than short conversational episodes, agents will inhabit continuous streams spanning months or years—like human development. A health agent could monitor patterns over time, adapting recommendations based on long-term trends. An educational agent could track language learning progress across years, continuously refining its teaching methods.

2. Grounded Actions and Observations: Instead of only text-based dialogue, agents will interact through rich sensorimotor channels—controlling digital tools, operating laboratory equipment, monitoring real-world sensors. This mirrors Piaget’s emphasis on sensorimotor grounding in cognitive development.

3. Reality-Based Rewards: Moving beyond human preferences and judgments, agents will receive feedback directly from the environment. A scientific agent pursuing climate goals would use actual CO₂ measurements, not human opinions about experimental designs. This grounds learning in reality rather than human prejudgment—allowing agents to discover approaches that humans might underappreciate or fail to recognize.

4. Experience-Grounded Reasoning: Rather than imitating human chains of thought, agents will develop their own methods of reasoning, grounded in and tested against reality. AlphaProof demonstrated this by learning to prove mathematical theorems in ways fundamentally different from human mathematicians—generating 100 million formal proofs after exposure to just 100,000 human-created ones, ultimately achieving medal performance at the International Mathematical Olympiad.1314

Early Signs: When Experience Surpasses Imitation

We’re already seeing glimpses of this transition. AlphaProof didn’t just learn mathematics from human examples—it learned by doing mathematics, generating its own proofs through interaction with a formal proving system. Similarly, DeepSeek’s recent work shows how “rather than explicitly teaching the model on how to solve a problem, we simply provide it with the right incentives, and it autonomously develops advanced problem-solving strategies.”13

This mirrors exactly how children learn. A toddler isn’t taught a theory of gravity—they construct it through dozens of dropping experiments. Similarly, these AI systems construct mathematical understanding through thousands of proof attempts, learning from success and failure.

The Piaget-RL Connection: Why This Matters

The convergence between Piaget’s developmental psychology and modern reinforcement learning is profound:

| Piaget’s Concepts | RL/Experiential AI Equivalent |

|---|---|

| Schemas | World models that predict consequences of actions |

| Assimilation/Accommodation | Value function updates vs. model restructuring |

| Sensorimotor stage | Grounded interaction with environments through actions and observations |

| Object permanence | Learning temporal persistence and causality through experience |

| Learning from surprise | Prediction error as learning signal |

| Action → Consequence | Agent actions receive environment feedback |

Both frameworks recognize that intelligence is not knowledge transfer but knowledge construction through experience. The key insight: cognitive structures emerge from the repeated cycle of prediction, action, observation, and adaptation.

Current Work and Future Directions

Recent research begins incorporating these principles. Del Ser et al. (2025) propose a framework integrating six key areas essential for enabling AI systems to develop structured, adaptive representations inspired by Piaget’s cognitive development theory:15

- Physics-informed learning: Embedding physical laws and constraints

- Neurosymbolic AI: Combining neural pattern recognition with symbolic reasoning

- Causal inference: Modeling interventions and counterfactuals

- Open-world machine learning: Handling novelty and continual learning

- Human-in-the-loop: Guided development with human feedback

- Responsible AI: Ethical constraints and safety considerations

These directions address Piagetian concerns: grounding in physical reality, structured causal representations, accommodation mechanisms, and experiential learning loops.

The convergence is striking. Both Piaget’s developmental psychology and modern reinforcement learning research point to the same insight: intelligence emerges from the interaction between the agent’s actions and the environment’s responses. Classic RL concepts—value functions, exploration strategies, world models, temporal abstraction—provide computational mechanisms for what Piaget observed in children: building internal models, testing predictions, learning from surprise, and reasoning over increasingly long timescales.13

Recent systems like Anthropic’s Claude with computer use, Google’s Project Mariner, and OpenAI’s Operator represent early steps toward agents that interact with digital environments through the same interfaces humans use—clicking, typing, navigating—rather than just conversing.13 These are the first stirrings of genuine sensorimotor grounding in AI.

Conclusion: The Hard Truth About Intelligence

Current AI development has optimized for benchmark performance and scaling—bigger models, more data. But both Piaget’s framework and emerging research reveal this approach’s fundamental limitations:

Quantity of text data ≠ Quality of experiential learning

A child constructs rich causal understanding from limited but highly informative experiences—each grounded in reality, tied to action and consequence, testable through prediction and surprise. Training on trillions of text tokens provides vast linguistic patterns but no sensorimotor grounding, no action-consequence loops, no reality-based surprise.

The challenge isn’t primarily technical—it’s philosophical. We want AI to be precocious, to skip development stages and emerge fully formed. But intelligence doesn’t work that way. Piaget demonstrated that genuine understanding is built slowly through countless interactions, mistakes, accommodation, and gradual construction of ever-more-sophisticated schemas.16

Yet there’s reason for optimism. The “Era of Experience” isn’t speculative—it’s beginning now. Systems are starting to learn through interaction with proving systems, code execution environments, and digital interfaces. The scale of experiential data is already eclipsing human-generated data in specific domains, and this trend will accelerate.13

The path forward is clear: If we want AI that truly understands reality rather than mimicking descriptions of it, we must let it learn through genuine experience—hands-on interaction, prediction, surprise, and patient construction of causal models grounded in reality itself.

As Alan Turing recognized and Piaget formalized, as Silver and Sutton now champion: machines that truly think must learn from experience—from things that actually happen, not just from reading about what happened.1113

The exciting truth is that we’re not just theorizing about this future. We’re building it, one interaction at a time, watching AI systems rediscover what every toddler dropping a toy already knows: the world is the best teacher, and experience is the only path to genuine understanding.

References

Additional Reading

- Boden, M. A. (1979). Piaget. Fontana/Collins.

- Brainerd, C. J. (1978). Piaget’s Theory of Intelligence. Prentice-Hall.

- Ginsburg, H., & Opper, S. (1988). Piaget’s Theory of Intellectual Development (3rd ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Lake, B. M., Ullman, T. D., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Gershman, S. J. (2017). “Building machines that learn and think like people.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 40, e253.

- Marcus, G. (2018). “Deep Learning: A Critical Appraisal.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1801.00631.

- Wikipedia contributors. (2025). “Piaget’s theory of cognitive development.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piaget’s_theory_of_cognitive_development

-

Piaget, J. (1954). The Construction of Reality in the Child. Basic Books. [Original work published 1937] ↩

-

Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. International Universities Press. ↩

-

Piaget, J. (1970). Genetic Epistemology. Columbia University Press. ↩

-

Piaget, J. (1936). The Origins of Intelligence in the Child. Routledge & Kegan Paul. (See also: Simply Psychology. (2025). “Piaget’s Theory and Stages of Cognitive Development.” Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/piaget.html) ↩

-

Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1969). The Psychology of the Child. Basic Books. ↩

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2023). “Cognitive Development.” StatPearls. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537095/ ↩

-

Piaget, J. (1959). The Language and Thought of the Child (3rd ed.). Routledge & Kegan Paul. ↩

-

Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1956). The Child’s Conception of Space. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ↩

-

Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (1958). The Growth of Logical Thinking from Childhood to Adolescence. Basic Books. ↩

-

Piaget, J. (1970). Piaget’s Theory. In P. H. Mussen (Ed.), Carmichael’s Manual of Child Psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 703-732). Wiley. ↩

-

Turing, A. M. (1950). “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” Mind, 59(236), 433-460. ↩ ↩2

-

Piaget, J. (1985). The Equilibration of Cognitive Structures: The Central Problem of Intellectual Development. University of Chicago Press. ↩

-

Silver, D., & Sutton, R. S. (2025). “Welcome to the Era of Experience.” In Designing an Intelligence. MIT Press. Retrieved from https://storage.googleapis.com/deepmind-media/Era-of-Experience%20/The%20Era%20of%20Experience%20Paper.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11

-

Masoom, H., et al. (2024). “AI achieves silver-medal standard solving International Mathematical Olympiad problems.” DeepMind. Retrieved from https://deepmind.google/discover/blog/ai-solves-imo-problems-at-silver-medal-level/ ↩

-

Del Ser, J., Lobo, J. L., Müller, H., & Holzinger, A. (2025). “World Models in Artificial Intelligence: Sensing, Learning, and Reasoning Like a Child.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.15168. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.15168 ↩

-

Flavell, J. H. (1963). The Developmental Psychology of Jean Piaget. Van Nostrand. ↩

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: